The worldwide environmental crisis caused by Western industrialisation and modernisation has been an international concern for half a century, yet the crisis has never been alleviated. On the contrary, it is deepening and becoming more variegated. In the 1960s, as more and more countries stepped aboard the high-speed train of industrialisation and modernisation, a counter-current quietly surged in Western civil society—an environmental movement critical of capitalist development emerged, call out for help on the Earth's behalf to save it from ecological destruction.

The worldwide environmental crisis caused by Western industrialisation and modernisation has been an international concern for half a century, yet the crisis has never been alleviated. On the contrary, it is deepening and becoming more variegated. In the 1960s, as more and more countries stepped aboard the high-speed train of industrialisation and modernisation, a counter-current quietly surged in Western civil society—an environmental movement critical of capitalist development emerged, call out for help on the Earth's behalf to save it from ecological destruction.

Environmentalists have at different times raised alarms about a range of different crises. In the sixties, it was chemical pesticides. Then the crisis of nuclear armament and nuclear energy caught people’s attention in the sixties and seventies. Acid rain was an issue that came up in the eighties. In the nineties it was logging and the depletion of the ozone layer, and today it is global warming. During all these decades, in addition to those advocates who called attention to the fact that economic globalisation is not sustainable, many people practiced what they preached by building ecovillages around the world to set examples of sustainability. They established the Global Ecovillage Network (GEN) in 1995 to lend support to like-minded people around the world in building their own experimental ecovillages or in conserving existing eco-communities that already have elements of sustainability.

In 1998, fifty ecovillage workers from around the world met in Denmark to launch a global educational movement for sustainable living. The experiences of the most successful ecovillages and eco-communities were summarised and developed into a curriculum which serves as a comprehensive guide to eco-community design. This curriculum, entitled Ecovillage Design Education (EDE), was launched in 2005. Since then many ecovillages and educational institutes have been conducting training courses on the principles and practice of creating sustainable eco-communities, after which the participants return to their communities to try creating experimental ecovillages or apply different kinds of relevant practices in their own countries or at their workplace.

According to the design of the EDE curriculum, the building of sustainable ecovillages is not concerned only with ecological sustainability but also with social, economic and spiritual values. The curriculum provides four keys to the understanding of the issues—worldview key, social key, economic key and ecological key, and there are five modules in each key (please read circle below).

A Worldview of the Interdependence of All Living Things

People who participate in the building of ecovillages embrace a holistic world view and realise that the universe is not a collection of objects but a communion of subjects that are interdependent. The harmonious relationship between human beings and nature is emphasised. It is believed that if human beings want to live in abundance, we have to become concerned with the relationship between human society and nature while reflecting on this relationship and the internal connection within our everyday life networks.

A Cooperative, Harmonious Society that Attaches Importance to Traditional Culture

Ecovillages attach importance to cooperation among inhabitants. The members of an ecovillage live together in a harmonious fashion while emphasising the diversity within the community. There may be differences in their cultural, spiritual and economic backgrounds but they explore the ways by which they may work, live and exchange as a community while accommodating cultural differences among themselves. Industrialisation and the globalised economic system have brought overconsumption and other side effects. Predatory individualism has led to social alienation and family breakdown. Community organisations modelled on traditional villages represent the most sustainable way of life that ecovillages can learn from. While liberalism and globalisation destroy diverse cultures and traditional customs resulting in a uniform consumerist culture, ecovillages attach importance to conserving indigenous and traditional culture and preserving the wisdom of older generations.

Economy as a Subsystem of Ecology

The EDE curriculum points out that in the mainstream development of current societies, “economics rules supreme as the ‘master discipline,’ with all other subjects and values subordinated to it”. Ecology is seen as the sub-system of economy rather than vice-versa. To attain the goal of sustainable development, this must be reversed and economy must become the sub-system of ecology. “The scale and nature of economic activities will be limited by the carrying capacity of the earth’s ecosystem.” Only then will we be able to create a more just and a more sustainable society which is ecology-centred.

In this kind of society, small scale self-reliance is the mode of production that would best meet the carrying capacity of the earth.

Conventional criteria such as the volume of the flow and growth of capital (such as Gross Domestic Product) will not be considered the indexes for economic and social development. They will be replaced by other indexes such as quality of life, sense of happiness and ecological development, etc. Enterprises will take the form of social endeavours which, apart from making profits, also aim to meet ecological and social development goals.

Safeguarding Local Environment and Ecology

Ecovillage designers put much effort into ensuring that the natural functions of all forms of life of a habitat are conserved and strengthened. The ultimate goal of any sustainable housing design is to build “living systems” that are self-reliant, self-maintaining and self-regenerating. A habitat and the local environment that supports it are interdependent and mutually beneficial. Building construction in ecovillages uses green technology and emphasises health, energy conservation and environmentally friendly structures while employing traditional skills and local technology. A major aim of the ecovillage is to increase the proportion of food that is produced, distributed and consumed locally. Use of appropriate technology is an important factor and the emphasis is on low cost, durability, low energy input, low maintenance cost, safety, local production and the implementation of plans that are most efficient in terms of energy consumption. Practical actions are taken to restore the natural environment where it has been destroyed; for example, planting trees, building topsoil, and restoring damaged riparian habitat.

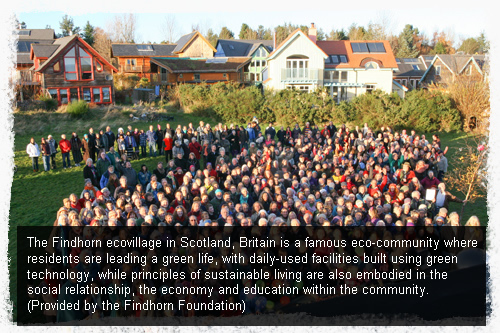

It can be seen from the above that the EDE curriculum covers spiritual transformation of the individual (holistic worldview) as well as a blueprint for an ideal society (the social, economic and ecological dimension in an ecovillage). Since the launch of the curriculum in 2005, over 3,000 persons from 30 countries have taken part in the training. They have returned to their own countries and workplaces to take part in the building of varied forms of ecovillages or related initiatives. There are now a number of experimental ecovillages in different parts of the world. Among the more renowned ones is Findhorn in Scotland, UK ( http://www.findhorn.org/).

The global ecological crisis escalates as the train of globalisation rumbles on at full speed. To reverse it is indeed a formidable task. The EDE curriculum maintains that the solution lies in the awakening of human beings and in realisation of their potential. The most effective way of achieving this is “global education”. Learners participating in the training will spread consciousness and wake others, just like “seeds in the wind that are spread all over the world”—“once fertile ground is found, a progress that is more organic, holistic, integrative and holographic will manifest itself…..”, and a global movement to build ecovillages will gather force in silence.

Websites for reference: