|

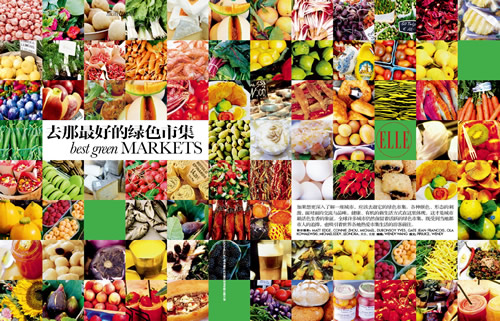

| The media report’s perspective: Organic green produce market is a symbol of a kind of city life. (EllE Magazine) |

Chang Tianle (Convenor of Beijing Organic Farmers Market)

CSA has been in China for 12 years, if we take as the starting point the Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) exchange sessions co-organised in Beijing by PCD and Han Hai Sha in 2003. (Han Hai Sha is an NGO in Mainland China promoting sustainable living.) In these 12 years, CSA, though originally a foreign concept, has slowly established itself locally as a grassroots movement, which is a crucial aspect of the growth of the movement, and is practiced by local producers, consumers, academics, and NGOs. Looking back on the last 12 years of CSA's communication work may help us to understand the movement's development pattern, and provide a reference point and directions for the next 12 years to come.

From 2003 to 2008, PCD seemed to be the only external force pushing CSA in the Mainland. The organisation nurtured and inspired many groups practising CSA in Beijing, Guangzhou, Guangxi, Chengdu, etc. Through workshops, exchange meetings and other means, it allowed people working in the same trade to reflect critically on the problems of conventional agricultural practices and to explore alternatives. Publications like Fragrant Soil and Enrooting Our Dream released during that period reflected these sentiments. Even though the CSA message was only circulated in a small circle, these publications and activities were able to mobilise a much-needed group of young people by giving them comprehensive information, and this facilitated the subsequent rapid expansion of CSA.

Consumer awareness of Food Safety Issues

The explosion of food safety-related scandals in 2008 led to a rise in consumer awareness of food safety and increasing concerns over the source of the food people were putting on their dining tables. Little Donkey Farm in Beijing was originally the Rural Reconstruction Centre of Renmin University of China, and an agricultural research base in Beijing’s Haidian District. When Professor Wen Tiejun, expert in ‘three rural issues’ (issues about agriculture, farmers and rural areas) visited the U.S. and got to know the CSA and the work it does in the U.S., he sent Shi Yan, then a PhD student, to intern at a CSA farm in the U.S. for half a year as recommended by the Institute for Agricultural and Trade Policy. On returning, Shi Yan joined Little Donkey Farm, and ran it with the U.S. CSA farms as a model. The right timing (with public concern over food safety issues), right locality (Beijing as the capital), and right people (Shi Yan 's special status (1) as an overseas returnee), made Little Donkey Farm an important flag-ship CSA body in China, and the mainstream media gave it extensive coverage, allowing the Rural Reconstruction Movement and the CSA model it advocated to achieve mainstream recognition. Many new farmers and rural youth returning to villages were so inspired that they started working with CSA.

Despite CCTV’s in-depth reporting on CSA, coverage of CSA’s revolutionary effect on conventional agricultural practices has been limited. When she interned at the Little Donkey Farm, Hu Xiaosheng selected and analysed 86 out of the 300-400 news reports made from 2008 to 2013. She found that the reports typically over-emphasised the personal story and short term financial gain in five ways: weighting the story towards Shi Yan at the expense of the importance of team work to CSA; stressing commercial elements but side-lining public interest; emphasising agriculture but overlooking the community; outlining operations but taking its goals lightly and lacking analysis on the impact of micro policies on macro policies. She attributes these to the media's tendency of favouring personal stories and relying on stereotypes, and considers her findings to have illustrated that CSA was too complex for the media to fully understand through only one or two reports.

Effect of the mainstream media and its blind spots

From 2011 onward, farmers’ markets, a new CSA practice, started to flourish in Mainland China. As farmers showed up regularly in cities, they also brought CSA issues with them, which set off a new wave of media coverage. Using Beijing Organic Farmers Market as an example, they attracted a total of 200 media reports from 2011 – 2014, including fashion and life style newspapers and magazines, as well as serious political and economic journals. The news reports could be divided into three categories in general: those that described the farmers markets as a new kind of lively and vibrant vegetable market; those that explored the operation models and certification processes behind these markets; and also those that followed up by asking what the deeper social implications were behind these markets (such as food safety, food autonomy, and urban-rural mutual support). Television reports were more simplistic and superficial, yet given its broad audience base it allowed the public to see the farmers and their markets for themselves.

2011 was also a successful year for Weibo and other social media. Communications were no longer limited to conventional media. Almost every CSA farm and farmers market was actively broadcasting their own news, interacting with fellow farmers, consumers, and people in the streets directly from their own Weibo accounts. In fact, CSA's characteristic emphasis on the connection between producers and consumers had long determined that new social media and ‘we-media’(2) would be of great help to its development and propagation. Weibo, for example, is easy to use, very low in cost and relatively unrestricted; it is good for sharing, broadcasting, and liaising between consumers and producers, and the effects of communication were easy to monitor. However, the 140-character restriction on Weibo messages' renders it difficult to broadcast in-depth posts, causing a loss of influence and usage after 2013.

Social media promotes pro-active action

Another social media platform that gained popularity at the time was WeChat, which has become the primary communication and information platform of many smartphone users. However, the drawbacks of WeChat include its comparatively narrower audience and thus its unsuitability as a news source. Public accounts on WeChat have to to use more professional words and pictures, also better edited and produced video clips, and thus raise the cost in communication for CSA members.

At the same time, many CSA practitioners started to realise that communication was a fundamental part of CSA, and should be embodied in different aspects of its work. For example, Beijing Organic Farmers Market manages its Weibo and WeChat accounts, as well as cooperating with conventional media. It is able to manage promotion through organising various gatherings - farmers’ markets, potlucks, recipe sharing events and second-hand bag sales - which receive considerable attention from conventional and social media alike.

A sense of humour for informative promotion

Beijing Organic Farmers Market also attempted to use light hearted and humorous ways to circulate their information. In 2014, it created a Weibo image using a bent and a straight cucumber with the caption: “If I were crooked, would you still love me?” Through this image, the Farmers Market wanted its consumers to realise natural farming would not always produce ‘standard’ vegetables, and that the shape of the vegetable would not determine its quality. Consumers should instead accept these vegetables’ outer imperfections, so as to reduce waste and to reduce use of the pesticides and growth hormones which are needed to meet consumer demand for good looking vegetables. Guangxi's CSA member Ainong Hui [literally meaning the ‘Love Farming’ Club] employed humour in their promotion, to great success. Their restaurant ‘Tushengliangpin’[literally meaning Local Good Food] described their anti-GMO work as ‘gao fei ji’- literally meaning ‘going without GMO’ but sounding in Mandarin like ‘making an airplane’. They hung a banner in the restaurant saying “ I only want to “gao fei ji”quietly”, to encourage their consumers to purchase ecological locally grown crops.

Guangzhou's Nurture Land was a good example of communication amongst CSA practitioners. Part of their sales came from their Weibo and WeChat shops. Each WeChat image and caption and each item in the shop were considered a marketing opportunity. In its product introduction, consumers would read about stories of food producers and the production mode of agrarian food. Then in WeChat, they would further explain the social and environmental reasons for supporting small-scale farmers engaging in ecological farming. This not only allowed them to stand out from the crowd of online shops, it also educated its consumers.

Three things to ponder for the future

Looking back over the communications work done by CSA practitioners in China, even though they all had only very limited resources, they made the best of their various advantages to spread the word via different media. (Apart from Nurture Land and Little Donkey Farm, no other organisations had specialised communications personnel.) In 2014, WeChat official accounts like ‘People’s Food Sovereignty’, ‘Soil Watch’ and ‘Groundbreaking Workshop’ proliferated to promote their courses, and yet it was evident at the same time that CSA's communications were hitting a bottleneck and facing challenges.

The first challenge lay in the difficulty of delivering complex subject matter. With concerns over food safety receiving more media and consumer attention, the aim is to encourage audiences to consider the bigger picture in relation to food production - for example issues such as small-scale farming, sustainability, food sovereignty and urban-rural interaction - in language that will make these complex issues easy to understand. Good communication is not just about getting hold of the right communication tools, channels and techniques; it also requires the production of quality content, including knowledge and thoughts to stimulate public discussion and tackling misconceptions relating to food production and agriculture: to find and re-instate the missing causal link for food safety; and to pinpoint the false propositions and misleading perspectives about it held in the mainstream narratives. This requires more sensitivity and research in communications in the CSA sector.

The second challenge is about how to consolidate disorganised and non-systemic communications. Would it be possible for CSA in the mainland, Taiwan and Hong Kong to orchestrate some concerted actions to generate better communication results? This would require better internal communication within the CSA community, and also requires raising communications work to the level that is necessary for the success of this social experiment.

Establishing a good collaborative basis between these three regions would recognise that they are facing very similar crises and challenges, and also that they share the same roots and bear similar characteristics. By learning from each other, CSA practitioners and the public can better understand the common crisis caused by the impact of economic development on agriculture everywhere, and can have more sympathy for the CSA movement, which is a movement resisting the mainstream conventional agricultural and economic system, after the public has got to know CSA’s mission.

The third question is, as CSA in the mainland still lacks a holistic communications platform and foreground, is it possible for a new platform to emerge to represent the CSA community, similar to Taiwan's Reveals Books (a publishing company featuring on agricultural and land issues) and News & Market (an online platform integrating agricultural news reporting and sales of agricultural products)? The best collaborative platform for communications is no doubt a jointly-operated media platform. It would be a media platform and at the same time a place for members of the CSA community to build mutual understanding, as they exchange views and learn from each other. If members used such a platform to discuss agricultural issues and to defend CSA from challenges posed by modernism, CSA’s communication work could make a greater impact, and thus help to resolve the first two problems.

We are counting on our colleagues in the CSA sector make the kind of promotional work listed above a reality.

Note:

- ‘Join-the-team’ (cha dui) refers to the 1960s policy in Mainland China of sending young urban intellectuals to rural or agricultural areas to “learn from the masses”. Since the 1980s, the term ‘joining the foreign team’ was used to describe people going overseas to work (not usually on farms). This expression was used about Shi Yan, as she went to work in a farm in the U.S.

- We-media is a term used in Mainland China for certain social media which are relatively independent compared with conventional and mainstream online media. We-media channels may be operated by either individuals or organisations, such as WeChat's public accounts, bloggers, Weibo accounts, etc.